We have long suspected that manager alpha is finite and tends to decay over time; our new research proves it

By Chris Woodcock, Essentia Head of Research and Product

Chris Woodcock leads the research and product teams for Essentia Analytics. Prior to joining Essentia, Chris was a technology analyst at GAM Investment Management and a hedge fund analyst at GAM Multi Manager in London. Before his career in financial services, Chris was a professional footballer with Newcastle United.

It is a well-worn trope in asset management that portfolio managers and analysts are prone to “falling in love” with their stocks.

Indeed, if you have been a professional equity investor, you’ll likely have uttered the words, at one point or at many, “It’s been a great company. I’m giving management the benefit of the doubt.”

There’s a big problem with stock-love, though. It’s a common cause of a very real (and very costly) issue: alpha — the excess performance a manager’s skill can bring to a portfolio — tends to decay over time, punishing managers who hold on too long.

The notion of an alpha lifecycle isn’t new; we have been studying it at Essentia since our earliest days as a company, and so have many of the world’s best investment risk teams. But the alpha lifecycle hasn’t been precisely quantified, across a diverse group of real equity fund managers, until now.

Essentia is wrapping up a 5-month analysis of this phenomenon, involving data from 42 portfolios over more than 10 years. The conclusions are clear: alpha has a beginning, a middle and an end. It tends to decay over time, reducing — or even reversing — the benefits it offered early on. Active managers who wish to deliver sustained alpha in their portfolios need to understand their own alpha lifecycles, and adjust their investment decision-making processes accordingly.

Picking good stocks is extremely hard. Of all the managers we’ve seen, even the best get it right no more than 60% of the time. Alpha is often measured in tiny basis-point increments, and it is frustratingly difficult to sustain, replicate and sometimes, even to explain.

But alpha is real: managers with the right process and discipline can indeed add measurable returns above those of an index (or an index fund). We have seen this proven, time and again, in our clients’ data. But what we have also observed is that the alpha decays, and the best fund managers are those who are good at recycling capital before that decay turns to rot

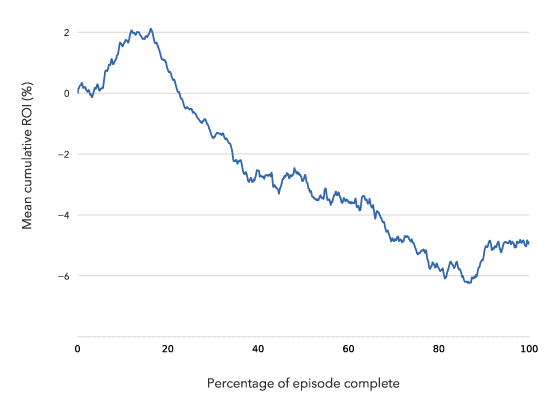

The chart below is from a client analysis we did back in 2014, and it illustrates the alpha lifecycle vividly: this equity manager chose stocks that added value for the first 60% of his typical holding period. After that, decay set in, leading to significant losses.

Our hypothesis back then, based on our own experience running money, was that fund managers were prone to the endowment effect: they were falling in love with their stocks, and holding on to them far longer than optimal. [1]

Since that time, we have been watching closely for signs of alpha decay in our clients’ portfolios, and we have expanded the techniques we use to track it. Holding period is one of the metrics we scrutinize most intently, looking for any evidence that the longest-held investments are destroying value, or at least not creating as much value as the rest. We also watch exit timing to see if managers are holding on to stocks, successful or not, that are on the decline.

This new analysis is contained in a formal research project entitled The Alpha Lifecycle. We are in the latter stages of producing a full white paper on this work (UPDATE: the full paper is available here).

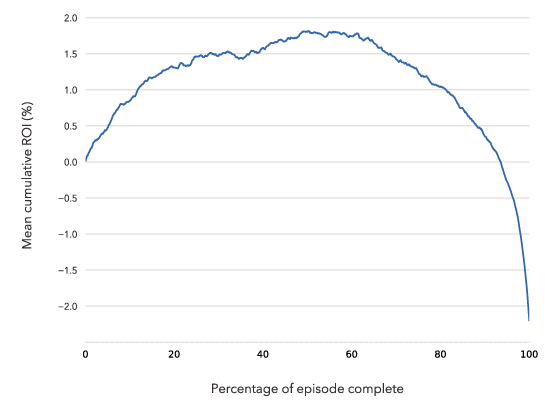

In the meantime, some highlights. While the new analysis shows a clear overall trend of long-term decay, at least four interesting manager alpha lifecycle profiles have emerged:

1. The Linear Accumulator

[Click image to enlarge]

First, there is a very linear alpha accumulator, sometimes with a small dip or period of stagnation early in the profile. These managers might be thought of as the heirs to Warren Buffett, consistently picking quality compounders that keep delivering for the long haul.

4. The Round Tripper

[Click image to enlarge]

The fourth and by far the most common profile is even more extreme version of what we observed in 2014: the inverted horseshoe. It dominates the analysis so much that, when combining all of the data from all of the fund managers under analysis, it is the overall picture we see.

For this analysis, we considered the return on investment (ROI), relative to that portfolio’s nominated benchmark, and how that ROI developed over time – (an episode in these charts refers to the life of a single investment, from the day the first share was bought to the day the final share was sold). We normalized the length of all investments over time, and took the average at every interval, to generate the charts you see above.

The bottom line? Our hypothesis from five years ago was correct: Alpha has a lifecycle, and tends to decay over time — frequently causing managers who fall in love with their stocks to suffer. On average, managers we analyzed experienced a 400 basis point peak-to-trough decay in return on each position. That’s the bad news. The good news is that this is low-hanging behavioral alpha fruit: excess return that can be clawed back by addressing one’s own behavior.

We can see it. It is identifiable, and quantifiable, through the various metrics and techniques we have developed since our first analysis. It’s also fixable – or, manageable, anyway: we can plot alpha lifecycle on a manager-by-manager basis, and deliver tailored nudges that notify the manager when a position is reaching what has historically proven to be the peak of alpha accumulation. He or she can then take this moment to assess the position using a different lens — and consider action before alpha decay sets in. We have recently developed the Essentia Alpha Decay Nudge, which offers this capability to our clients — and they are well aware of how powerful this is.

FOOTNOTE

[1] This was a reasonable assumption: endowment effect is one of the strongest, clearest cognitive biases ever observed (Kahnemann & Thaler’s original paper has been cited five thousand times in academic literature). The classic experiment involved mugs & chocolate bars; if students get attached to mugs, we reasoned, with everything we knew it felt plausible that investors would get attached to stocks. We set out to show this, and measure the ROI.