By Charley Ellis

Share post

Charley Ellis is an investment consultant and writer, dubbed “the wisest man on Wall Street” by Money Magazine. His book, Winning the Loser’s Game, was lauded by Peter Drucker as “by far the best book on investment policy and management.” Charley founded Greenwich Associates, an international strategic consulting firm focused on financial institutions. He has chaired Yale University’s investment committee and served as Chairman of the Board of the Institute of Chartered Financial Analysts.

Charley is a Non-Executive Director at Essentia Analytics.

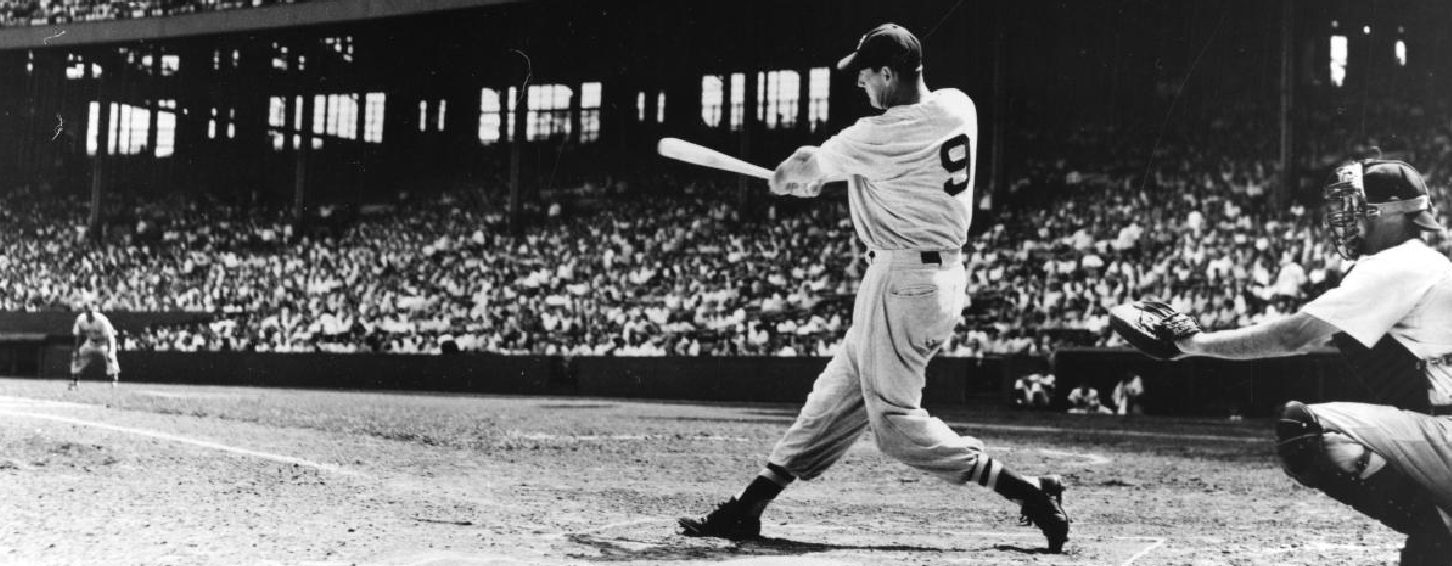

Ted Williams, gruff, aloof and taciturn, produced a great batting record over his 22 years of playing baseball, and wrote one of the best books on the sport, The Science of Hitting.

Filled with insights gained from intensive study, every analyst and portfolio manager would benefit from reading this superb compilation of lessons learned and how they can be applied to investing.

Ted Williams (1918-2002) was a professional baseball player for the Boston Red Sox. Six times American League batting champion, his career record would have been even better had he not been called to active duty in Korea in 1951-1952, the years in which – during the months he played ball – he averaged over .400.

It ain’t easy

Expert investors know that hitting home runs in the stock market is hard. So many complex judgements must be just right: estimation of future earnings produced by the confluence of myriad factors inside and outside the company; changes in other investors’ perceptions and projections; and estimations of future market valuations. That’s why investors are unusually well-positioned to understand Ted Williams’ assertion about the difficulties of hitting in baseball. “Hitting a baseball – I’ve said it a thousand times – is the single most difficult thing to do in sport.” That statement commands attention, particularly among competitive people in the notoriously competitive and constantly measured field of investment management.

First published in 1970 and then revised in 1986, The Science of Hitting is still widely read by novice and pro baseball players.

Having caught our attention, Williams continues. “I get raised eyebrows and occasional arguments when I say that, but what is there that is harder to do? What is there that requires more natural ability, more physical dexterity, more mental alertness? That requires a greater finesse to go with physical strength, that has as many variables and as few constants, and that carries with it the continuing frustration of knowing that even if you are a .300 hitter—which is a rare item these days—you are going to fail at your job seven out of ten times? If Joe Namath or Roman Gabriel completed three of every ten passes they attempted, they would be ex-professional quarterbacks. If Oscar Robertson or Rick Barry made three of every ten shots they took, their coaches would take the basketball away from them.”

As though he was talking about great stock pickers or portfolio strategists, Williams goes on, “Baseball is crying for good hitters… Hitting is the most important part of the game; it is where the big money is, where much of the status is, and the fan interest.”

Know thyself

Getting serious about getting better at hitting is not dissimilar to improving your skill as an investor. Williams explains: “Much of what I have to say about hitting is self-education. You, the hitter, are the greatest variable in this game of baseball. To know yourself takes dedication. That’s a hard thing to have. Today, ballplayers have a dozen distractions.” Every professional investor would agree with both points: we need to focus with dedication and we face too many distractions.

But, nodding our heads is one thing. Taking the right action is different. Williams had no patience with “natural” hitters. He knew better. As a serious student of hitting, he worked hard at figuring out exactly what did or did not work well. Williams experimented with different stances, tried different bats before settling on 33 ounces as best for him, and got the Red Sox to put a scale in the club house so he could check every bat’s weight. As he explained his attention to every detail that could affect his performance, Williams said, “bats pick up condensation and dirt lying around on the ground.”

Much of The Science of Hitting explains the “game theory” of interactions between pitchers and batters in different situations. But it is this area of what a hitter can do on his own to increase success that Williams offers his best insights: How many investment analysts and fund managers could up their own games by careful, objective study of their past decisions in search of imperfections to reduce or remove?

As a serious student of hitting, Williams worked hard at figuring out exactly what did or did not work well.

Charley Ellis

A better understanding of skill

The traditional view in baseball had been that there was a single strike zone – an understanding which colored how players and their performance were assessed.

Williams dismissed this, insisting instead that there were actually 77 different “mini zones” – seven columns of eleven little zones. And for each mini strike zone, he calculated his batting average. What a revelation! Williams’ batting averages varied from a mere .230 in the low and outside “mini zone” to a mighty .400 in his “happy spot.”

No wonder Williams’ first rule for success is: “get a good ball to hit!” As he explains, “A good hitter can hit a pitch over the plate two or three times better than a questionable ball in a tough spot. Pitchers still have to make enough mistakes to give you some balls in your happy zone. All hitters have areas where they like to hit. But you can’t beat the fact that you’ve got to get a good ball to hit!” Or as Warren Buffet often advises investors: “Wait for the fat pitch.”

Williams identified 77 different strike zones and a new approach for hitters to judge incoming pitches.

Do more of what you’re good at

Williams offers a series of tips on hitting that investors can readily convert to investing. As a serious student of his nearly 8,000 times at bat, Williams believed “every trip to the plate was an adventure – one I could remember and store up as information.” How many of us have the same joyful approach to our times at bat as investors? How many of us collect, categorize, and carefully analyze all our many decisions? And Williams not only studied with diligence his own many experiences, he studied other hitters. And he was committed to “practice, practice, practice. I hit until the blisters bled. It was something I forced myself to do. Extra batting practice is how you learn.”

Acknowledging that he had 20-10 vision – a most convenient advantage for a hitter – Williams sounds a lot like a winning investor reviewing his record of performance. “What I had more of wasn’t eyesight. I had a higher percentage of game-winning home runs than Ruth; was second only to Ruth in slugging and percentage combined; walked more frequently than Ruth and struck out much less.”

Then Williams goes on to say what every great investor knows is the secret of success: “I had to be doing something right and the principal something was being selective.”

Ted Williams was a very good batter. He made himself a great player by studying the game and, most of all, studying himself in unrelenting detail on every dimension. What a great lesson for anyone determined to excel – particularly in the major league of today’s professional investment management.